By Jon Chesto Globe Staff,Updated August 21, 2022, 5:44 p.m.

Davis Companies wants to clean up the contaminated site and fill it with a mix of housing, retail, and industrial uses.

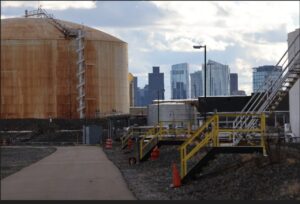

One of Greater Boston’s biggest developments in years is taking shape just north of the Boston city line, on a sprawling 95-acrefuel tank farm in Everett.

During the past few weeks, The Davis Companies has been sharing its preliminary plans for the ExxonMobil property. The Boston-based developer recently secured an agreement to buy the heavily contaminated site — technically several connected parcels, stretching from Sweetser Circle at the intersection of routes 99 and 16, down to the Mystic River waterfront.

Davis essentially is approaching the project as two distinct sections: a residential area, at the northern corner near Sweetser Circle, where apartments and ground-floor retail would be built, and an industrial area through the center of the property around Beacham Street, to feature warehouses as well as high-tech and life sciences manufacturing. The company envisions up to 2.4 million square feet that could be built relatively quickly under existing zoning, and another 2 million square feet or more that would evolve over time with the right market conditions and zoning changes. Davis has not yet disclosed plans for the property’s waterfront area.

City councilors welcomed the potential to clean up the property but raised concerns about traffic and school crowding during a meeting earlier this month with two representatives for Davis.

“It’s almost like we’re adding an adjacent city to the City of Everett,” city councilor Stephanie Martins said in an interview. “We need to really balance the existing and the new in a way that is sustainable.”

Everett Mayor Carlo DeMaria is among those who hope the Davis redevelopment can be the impetus to finally extend the Silver Line rapid bus service into Everett and maybe even prompt a train station to be built there. Tracks for the MBTA’s Newburyport/Rockport line traverse Everett near the ExxonMobil property, but there are no stops in the city.

“One of the most critical components of this project is the chance for us to attract new commercial businesses and job opportunities for our residents,” DeMaria said of the Davis project. “I also think that the size and scale of this type of development will help force the state to move forward with using federal dollars available to it for the public transit improvements that I have been advocating for over the past several years.”

The potential redevelopment of the ExxonMobil tank farm comes at a pivotal point in the metamorphosis of the section of Everett around Lower Broadway, transforming it from what was widely seen as home to a gritty industrial dumping ground on Boston’s doorstep to an entertainment destination with desirable housing and high-paying tech jobs. Wynn Resorts helped kick things off by opening its gleaming $2.6 billion casino and hotel in 2019 where a Monsanto chemical plant once stood, overlooking the Mystic. Wynn also bought land across Broadway (Route 99) for redevelopment, and is pursuing plans for a concert-and-conference venue for one of those properties, to be connected to Wynn’s Encore Boston Harbor casino by an overhead footbridge.

Meanwhile, Constellation Energy put a 40-plus-acre portion of its Mystic power plant property across from the casino on the market and hopes to wrap up that sale by the end of the year. Among the potential uses for that property that are being discussed: a stadium for the New England Revolution pro soccer team, owned by the Kraft Group. Constellation plans to eventually shutter the two remaining gas-fired units at the power plant in two years.

The biggest of all of these is the ExxonMobil property, which has been home to some form of petroleum storage and distribution since the 1920s.

Mike Cantalupa, chief development officer for Davis, told the city council that the developer will seek tax incentives or other public subsidies from city and state officials to help offset environmental remediation and infrastructure costs.

“The first and foremost issue on the site is to clean it up, and it comes at a tremendous cost,” Cantalupa said. “We like to think we bring creative solutions to complex problems. … We can’t be the sole provider but we need to solve them cooperatively and with the city’s input.”

Davis officials want to start with a 1 million-square-foot first phase with three buildings — 300 to 350 apartments in one, warehouse storage in a second, and advanced manufacturing in the third. (Davis is currently developing a warehouse next door, rumored to be for Amazon.)

At full buildout, Davis sees the potential for more than 4 million square feet of development taking place, including apartment towers and public green space — as well as labs and biomanufacturing, in part aimed at life sciences companies headquartered a short drive away in Cambridge.

“We don’t think this is your grandfather’s industrial park — buildings with solid block walls and you don’t know what’s going on inside the buildings,” Cantalupa said. “The buildings and the architecture need to be attractive.”

Reassuring city councilors’ concerns about schools and traffic could pose another challenge.

Martins, for example, ticked off a list of potential issues with the development on her campaign Facebook page on Wednesday.

She said a solid commitment from state officials for a new train station is imperative, as is a traffic mitigation plan to address the congestion along Route 99 and the Sullivan Square rotary in nearby Charlestown. She also wants to see a new fire and police substation built in the Lower Broadway area to accommodate all the new development.

“Anything seems better than what we have. I must say the cleanup, the remediation, are huge positives,” Martins said. “But whatever we’re bringing to the city must be done right.”